Adolescents From Divorced Families Frequently Display All of the Following Negative Effects, Except:

Suggested Citation:"ix Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Quango. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the U.s.: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/18613.

×

9

Consequences for Families and Children

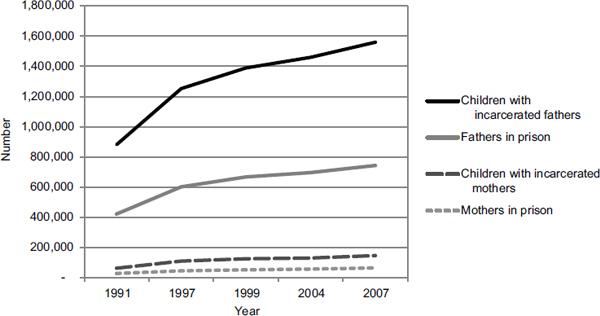

The dramatic increment in incarceration rates since 1972 has stimulated widespread involvement in how this trend is affecting families and children. As incarceration rates increased, more families and children had direct feel with imprisonment of a parent (see Figure 9-1). In a adding of the number of modest children with fathers in prison house or jail in the two decades from 1980 to 2000, Western and Wildeman (2009) plant that the number of children with an incarcerated father increased from virtually 350,000 to 2.1 million, about 3 percent of all U.S. children in 2000. Co-ordinate to the nearly recent estimates from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 53 pct of those in prison house in 2007 had pocket-sized children. In that year, an estimated 1.7 meg children under historic period xviii had a parent in state or federal prison (Coat and Maruschak, 2008). The racial and ethnic disparities of the prison population are reflected in the disparate rates of parental incarceration. In 2007, blackness and Hispanic children in the United States were 7.5 and 2.vii times more probable, respectively, than white children to take a parent in prison (Glaze and Maruschak, 2008; encounter too Box 9-one). While the consequences for families and children can be expected to vary by race and ethnicity, much of the research reviewed for this study does non distinguish outcomes by these characteristics. For the few studies that practice, the differences and similarities are noted in the text.

This chapter reviews the empirical testify on the consequences of incarceration for family behavior and kid well-beingness. We focus on incarceration of men considering it is more mutual than that of women and is the field of study of the bulk of the available inquiry. The literature on men's incarceration is big and includes ethnographic studies as well as quantitative

Suggested Citation:"9 Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the The states: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/18613.

×

Figure 9-i Estimated number of parents in state and federal prisons and their minor children, by inmate'southward gender.

SOURCE: Data from Glaze and Maruschak (2008).

analyses of survey data and administrative records. The literature on women'due south incarceration is limited but growing. Near of the literature examining the consequences of maternal incarceration for families and children is primarily qualitative or express to specific field sites. While the adventure of maternal imprisonment for children is quite small-scale, information technology has grown much more speedily in recent years than the risk of paternal imprisonment (Kruttschnitt, 2010; Wildeman, 2009). The number of children with a mother in prison house increased 131 percentage from 1991 to 2007 (run into Figure ix-1), while the number with a father in prison increased 77 percentage (Glaze and Maruschak, 2008). Equally discussed in Chapter vi, incarcerated mothers are more likely than incarcerated fathers to accept lived with their children prior to incarceration. In a 2004 survey of inmates, 55 percent of female inmates in state prisons who were parents, compared with 36 pct of male inmates, reported living with their children in the calendar month before arrest. Incarcerated parents in federal prisons were more than likely to report living with their children before arrest (73 per centum of female inmates, compared with 46 percent of male inmates). In addition, incarcerated mothers are more probable than incarcerated fathers to have come from single-parent households (42 percent versus 17 percentage in state prisons, and 52 percent versus 19 percentage in federal prisons) (Glaze and Maruschak, 2008).

The bachelor literature on the consequences of incarceration for families and children focuses on incarceration per se and does not examine the

Suggested Commendation:"9 Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United states of america: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: x.17226/18613.

×

BOX 9-1

Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Cumulative Hazard of Parental Imprisonment

Wildeman (2009) calculated the probability that a child would take experienced a parent being sent to prison house by the child's teenage years. This cumulative risk of parental imprisonment was calculated for two dissimilar birth cohorts of children. For white children born in 1978, Wildeman (2009) found that 2.ii to two.4 percent had experienced a mother or male parent beingness sent to prison past age 14. For a birth accomplice born 12 years afterward, in 1990, the cumulative risk of parental imprisonment for white children had increased to 3.6 to 4.2 percentage. Among black children, parental imprisonment in the 1978 cohort was 13.viii to 15.2 pct, compared with 25.1 to 28.four percent in the 1990 cohort. Similar estimates were developed by Pettit and colleagues (2009), who found that in 2009, 15 pct of white children whose parents had not completed high schoolhouse had experienced a parent being sent to prison house past age 17. Among Hispanic children with similarly depression-educated parents, 17 percentage had experienced parental imprisonment past age 17. The comparable percentage for African American children is 62 percent (Pettit et al., 2009).

specific effects of the increasing rates of incarceration. Therefore, nosotros cannot discuss any changes in the consequences for families and children of the incarcerated during this catamenia. We consider what is currently known nearly the potential consequences for individuals, positive and negative, every bit a result of having a partner or parent incarcerated and believe that the numbers affected accept risen. A few studies, however, discussed later on, look at the effect of increasing incarceration on the marriage market place and childbearing.

Most studies find that incarceration is associated with weaker family bonds and lower levels of child well-existence. Men with a history of incarceration are less likely to marry or cohabit and more probable to form unstable partnerships than those who have never been incarcerated, and children of incarcerated fathers tend to exhibit more than problems in childhood and adolescence. The picture is not entirely negative, withal. In that location is evidence from at least ane state, for example, that increased rates of incarceration are associated with lower rates of nonmarital childbearing. Moreover, some studies detect that the negative association betwixt incarceration and family outcomes is limited to families in which the father was living with the family prior to imprisonment. Finally, there is evidence that in cases in which a begetter is vehement, incarceration may actually improve his family's well-being. The few studies that have examined the consequences for children of incarcerated mothers tend to focus on separation from children and housing stability. These studies oft find persistent disadvantage in terms of poor

Suggested Citation:"ix Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United states of america: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Printing. doi: 10.17226/18613.

×

education and financial circumstances, substance corruption, mental affliction, domestic abuse, or a combination of these. At this time, findings on the furnishings of maternal incarceration on child well-being are mixed.

In this chapter, nosotros begin past reviewing available research on the consequences of men'south incarceration for families. We then examine the minor merely growing literature on mothers' incarceration. Next, we discuss the methodological limitations of existing studies in this surface area. The chapter ends with a review of cognition gaps and concluding remarks.

INCARCERATION OF PARTNERS AND FATHERS

For this review, we looked at both quantitative research and ethnographic studies. Our review of quantitative studies was express to studies published within the by decade1 that run into four criteria: (1) they are based on probability samples; (2) response rates are good, and sample attrition is depression; (3) they include good measures of incarceration and family/kid outcomes; and (four) the temporal ordering of incarceration and the outcome of interest is correct. We gave special attention to studies that attempt to deal with omitted variable bias. (For other reviews of the incarceration literature, see Hagan and Dinovitzer, 1999; Murray et al., 2009; Schnittker et al., 2011; Wakefield and Uggen, 2010; Wildeman and Western, 2010; and Wildeman and Muller 2012). Our review criteria would exclude most studies linking outcomes to the developmental stage of the kid(ren) because these studies typically are based on modest, purposive samples. As a result, our review represents a partial look at the literature on the consequences of incarceration for families and children.

Ethnographic studies by and large do not allow for statements almost causality; however, they draw the experiences of women with incarcerated partners and their children and reveal potential mechanisms for explaining the link between incarceration and family well-being. A cardinal goal of our assessment is to determine whether the employ of more complex statistical methods produces findings that are consequent with those from ethnographic studies and quantitative analyses using simpler statistical methods. To the extent that the findings from the various studies tell a similar story, nosotros accept greater confidence in the results.

In this department, we review the consequences of incarceration of men in four domains—(ane) male-female relationships, (2) economic well-being, (3) parenting, and (4) kid well-being.

_________________

iRecent quantitative work does a better task than older studies of bookkeeping or controlling for possible confounding and unmeasured variables.

Suggested Citation:"9 Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the The states: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Printing. doi: 10.17226/18613.

×

Male person-Female Relationships

An extensive body of qualitative inquiry examines relationship dynamics betwixt incarcerated men and their female partners. These studies notice that although these men view union as a desirable goal (Braman, 2004), incarceration (in addition to the father'due south criminal activity) poses difficulties for maintaining a relationship, and for those who are not yet married, information technology makes marriage less feasible than for those not incarcerated.

Relationship bug of the incarcerated are attributable to several factors. Outset, women abound weary of the time, energy, and money required to maintain a relationship with an incarcerated partner. Studies find that while family members oft view their office as i of moral and emotional support, making regular visits and telephone calls and sending letters and packages to prisoners tin be hard and plush (Grinstead et al., 2001), specially when visits require long-distance travel and hours of waiting (Christian, 2005; Condolement, 2003; Braman, 2004). 2nd, women may undergo emotional strain from not knowing what their partner is experiencing while incarcerated (Ferraro et al., 1983) or from feeling socially excluded (some report feeling as if they themselves were incarcerated). Upon visiting their partners, for case, women often are subject to searches, removal of personal belongings, and the enforcement of strict rules (Fishman, 1990; Comfort, 2003; Braman, 2004). Similarly, following release, partners may go subject to some terms of the parolee's supervision, such as searches of their residence or automobile (Comfort, 2008). Tertiary, either partner may perceive an imbalance in the relationship. Often, this is because men are unable to contribute as much financially while incarcerated. However, Braman (2004) finds that the perceived imbalance is not always material. Incarceration may diminish trust between partners and augment the perception that individuals demand to look out for themselves get-go, that others are selfish, and that relationships are exploitive. Moreover, Goffman (2009) finds that former prisoners and men on parole may feel the need to avoid or advisedly navigate their relationships with partners who may utilise the criminal justice organization as a way to control their behavior (east.g., a woman may threaten to telephone call her partner'southward parole officeholder if he continues arriving home late, becomes involved with another woman, or does non contribute enough coin to the household). In communities with loftier levels of incarcerated males, the overall gender imbalance also may shape behavior, making men more inclined to seek other partners (Braman, 2004).

Despite these findings, it is important to note that incarceration is not always harmful to relationships. Edin and colleagues (2004) find that while incarceration may strain the bonds between parents who are in a relationship prior to incarceration, it more frequently proves beneficial to couples whose relationship has been significantly hindered by lifestyle choices (almost

Suggested Citation:"9 Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the U.s.a.: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: ten.17226/18613.

×

always substance corruption) prior to incarceration. For some of these men, incarceration serves as a turning point, a fourth dimension to rehabilitate and rebuild ties with their child'south mother—at least a cooperative friendship if not a romantic relationship. There is likewise testify that marriage prevents dissolution of relationships. Indeed, Braman (2004) reports that wives of incarcerated men oftentimes say they would take left their husband had they not been married to him.

Consistent with the ethnographic literature, quantitative studies find that incarceration increases the economical costs of maintaining a human relationship and imposes considerable psychological strain on the wives and partners of men in prison house, especially those who were living with the man prior to his incarceration. At the same fourth dimension, these studies highlight the fact that for some couples, prison is a time when men tin can change their lives and reestablish family relationships. A large number of quantitative studies take examined the association betwixt incarceration and such behaviors as marriage, cohabitation, divorce, and repartnering (Apel et al., 2010; Charles and Luoh, 2010; Lewis, 2010; Lopoo and Western, 2005; Massoglia et al., 2011; Turney and Wildeman, 2012; Waller and Swisher, 2006; Western and McLanahan, 2001; Western et al., 2004). One study examines nonmarital childbearing (Mechoulan, 2011). Some of these studies focus on young adults or men in full general, while others focus on parents just. All conform for observed characteristics, and many employ rigorous methods.

Lewis (2010) and Waller and Swisher (2006) find show that fathers' incarceration reduces subsequent matrimony and cohabitation. More rigorous studies, nevertheless, suggest that these effects are non causally related. Using a lagged dependent variable (LDV) model, Lopoo and Western (2005) notice no association between men'south incarceration and afterwards marriage. Similarly, using data from a accomplice of Dutch men bedevilled of a crime, Apel and colleagues (2010) find no outcome of incarceration on marriage after the first year postrelease. Both studies do, however, find a strong positive effect on divorce/separation. Married men who were incarcerated were 3 times more than likely to divorce than married men who were convicted but not incarcerated. These researchers also report that the effect of incarceration on divorce was stronger among men without children and those bedevilled of serious offenses. This study is specially noteworthy because, past focusing exclusively on men with a criminal conviction, it can distinguish the effects of incapacitation from those of confidence.

Ii studies use state-level variables to examine how variation in marriage market conditions due to increasing incarceration rates touch women'southward marriage and fertility. Using state-level, race-specific incarceration rates as an indicator of wedlock market conditions, Charles and Luoh (2010) discover a negative effect of incarceration on the prevalence of marriage among women. They besides find a modest and positive effect of incarceration on

Suggested Citation:"9 Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Quango. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the Us: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: x.17226/18613.

×

women's didactics and labor force participation. Using a similar approach but more detailed information on mothers' behavior, Mechoulan (2011) finds a weak negative effect of male incarceration on black women'south probability of spousal relationship and a strong negative issue on young black women'due south nonmarital childbearing. This study besides finds a positive link between men'due south incarceration and women's education and employment. The Mechoulan study is of item interest because it highlights the possible benefits of high rates of male incarceration: namely, more education for women and the prevention of unintended pregnancies among young black women. The author is careful to annotation that his analysis does not place the mechanisms underlying these changes in women's behavior, which could be due to the increased incapacitation of more than promiscuous men or changes in women's sexual beliefs. The author also notes that his findings are driven primarily by changes in incarceration rates in one land—Texas—making it hard to generalize to other parts of the The states.

In addition to the studies described above, which focus on men rather than fathers, at least 1 study attempts to approximate the effect of fathers' incarceration on the stability of parents' unions. Using information from the Delicate Families Study, Turney and Wildeman (2012) notice that father'south incarceration increases the likelihood that the mother will terminate her relationship with him and class a partnership with a new human. The researchers aim to place the issue of incarceration by employing a rich set of control variables (including couple's relationship quality); they also limit their sample to couples in which the father has a history of incarceration and compare couples who experienced a recent incarceration with those who did not. The latter results can exist interpreted equally the effect of a repeat incarceration for men with a history of imprisonment.

The studies described above have several limitations. Kickoff, those that use state-level incarceration rates to guess the effect of incarceration on marriage and divorce must assume that marital status does non affect incarceration (whereas many people would argue it does) or that a 3rd variable—such as social norms—is non causing both high rates of incarceration and high rates of union instability. A 2d limitation of well-nigh studies is that they ignore unions formed by cohabiting couples. Considering marriage is rare among men at high risk of incarceration, at to the lowest degree in the U.s., the failure to include cohabitating unions makes information technology difficult to draw strong conclusions about the effect of incarceration on union stability. A third limitation is that nigh studies do non compare the consequence of incarceration with that of other types of forced separation. The 1 study that makes this comparison (Massoglia et al., 2011) finds that the destabilizing furnishings of incarceration are similar to those of armed services deployment, which suggests that the negative consequences of incarceration are due not to stigma but to the stress associated with incapacitation or maybe changes in fathers'

Suggested Citation:"9 Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: ten.17226/18613.

×

behavior. Both war and incarceration are likely to expose men to violence and undermine their relationship skills.

Economic Well-Beingness

Co-ordinate to the Agency of Justice Statistics, more than half of fathers in country prison report existence the primary breadwinner in their family unit (Glaze and Maruschak, 2008). Thus the partners and children of these men are likely to experience a loss of economic resources while the provider is in prison. This effect also is likely to persist subsequently the male parent returns home, given what is known about the link between incarceration and unemployment (encounter Chapter 8). Ethnographic studies generally concur that the incarceration of a partner or father tin atomic number 82 to increased economic hardship for members of his family. Financial circumstances are one of the virtually frequently cited sources of stress or strain amidst partners of incarcerated individuals (Carlson and Cavera, 1992; Ferraro et al., 1983). Many affected families already were living in unfavorable economic circumstances prior to the incarceration, and many were dependent on public aid or other financial support. Nonetheless, Arditti and colleagues (2003) observe that these families become even more impoverished post-obit the partner's or father'south incarceration.

The increased economical stress amongst families affected past incarceration is due to several factors. One is the extra expenses (collect calls, travel costs, sending money and packages) reported past women trying to maintain a relationship with the incarcerated private (Grinstead et al., 2001; Christian, 2005; Arditti et al., 2003). Other new expenditures include attorney or other legal fees or job loss stemming from increased work-family disharmonize (Arditti et al., 2003).

Consequent with the ethnographic literature, quantitative studies indicate that the families of men with an incarceration history experience a good deal of economic insecurity and hardship, resulting in greater use of public assistance among mothers and children. Three studies examine the link between fathers' incarceration and mothers' material hardship (including housing insecurity) (Geller et al., 2009; Geller and Walker, 2012; Schwartz-Soicher et al., 2011); two other studies examine the relationship betwixt fathers' incarceration and mothers' welfare use (Sugie, 2012; Walker, 2011); and 1 written report examines the clan between fathers' incarceration and children's homelessness (Wildeman, forthcoming). All of these studies are based on data from the Frail Families Study.

Geller and Walker (2012) find that the partners of incarcerated fathers are at increased adventure of experiencing homelessness and other types of housing insecurity. These authors use a lagged measure of housing insecurity and a rich set up of early-life and contemporaneous covariates. They also

Suggested Citation:"nine Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Quango. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the U.s.a.: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/18613.

×

distinguish between recent and early on incarceration and find that function of the consequence of incarceration on housing insecurity is due to a reduction in financial resources (father's earnings or partner'south financial contributions). In a third written report examining housing insecurity, Wildeman (forthcoming) uses propensity score models and finds that recent paternal incarceration is associated with an increased risk of child homelessness, especially among blackness children. Foster and Hagan (2007) too find an association with increased homelessness among boyish girls.

One study in this group examines the influence of fathers' incarceration on other types of material hardship too housing. Employing several strategies for determining causality, including stock-still effects models, a lagged dependent variable, and a placebo test used to examine whether future incarceration is related to current behaviors, Schwartz-Soicher and colleagues (2011) find stiff evidence that paternal incarceration leads to increased fabric hardship for mothers and children, measured as mothers' reports of the difficulty faced by their family in coming together basic needs. Finally, two studies examine whether fathers' incarceration increases mothers' participation in public assistance programs. Using propensity score matching, Walker (2011) finds some testify that incarceration may increase the probability of mothers' receipt of both food stamps and Temporary Assist for Needy Families (TANF). In dissimilarity, using stock-still furnishings models and a more recent wave of data, Sugie (2012) finds that recent paternal incarceration is associated with mothers' receipt of nutrient stamps and Medicaid/State Children's Wellness Insurance Program (SCHIP) help, but not TANF. Neither of these studies attempts to judge the cost of these benefits to taxpayers. On rest, the evidence that father's incarceration increases the family unit'southward material hardship and housing insecurity is stiff, especially when the male parent was living in the household prior to incarceration.

Parenting

Ethnographic work examining the effects of incarceration on parenting focuses primarily on fathers, including their contact with the kid and their financial contributions to the family unit. In discussing these findings, it is of import to annotation that men do not begetter in a vacuum. Key concepts that influence the experiences of an incarcerated begetter and his children are his relationship with the child'southward mother and his ain behavior and lifestyle before his arrest.

The male parent'south relationship with his kid's mother appears to play an important role in the father-child relationship during incarceration and later his release from prison. Fathers who lived with their child prior to incarceration are more likely than nonresident fathers to stay in contact with the child (Martin, 2001). In addition, while some mothers and families

Suggested Citation:"9 Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: x.17226/18613.

×

provide encouragement for continuing contact between the child and his or her father, others promote social exclusion (Nurse, 2004). For instance, some family members refuse to bring the child when making visits (Martin, 2001), and some fathers experience that mothers use the incarceration to justify limiting or prohibiting contact or painting a negative view of the father so the kid does not want to interact with him (Edin et al., 2004).

The father's lifestyle prior to his incarceration and the quality of the father-child relationship also are of import influences on the parenting effects of incarceration. As Edin and colleagues (2004) note, if the father's severe substance abuse or criminal activeness prior to incarceration was enough to prevent him from making financial contributions to the family unit or developing a shut human relationship with his kid(ren) prior to his abort, then his incarceration may serve every bit a fourth dimension to rebuild bonds, even allowing parents and children to communicate more oftentimes (Giordano, 2010). Some fathers believe their incarceration will serve as an example to their children, discouraging them from making similar mistakes (Martin, 2001). On the other hand, among fathers who previously experienced frequent contact with their children, incarceration almost always proves to exist detrimental—breaking bonds in terms of physical closeness and financial contributions and eroding relationships that may already accept been fragile. Most often, this is considering the female parent ends her human relationship with the father or becomes involved with some other homo (Edin et al., 2004). Martin (2001) too finds that fathers themselves sometimes refuse to accept visits from their child(ren) to protect themselves and their child(ren) emotionally.

4 quantitative studies examine the association between fathers' incarceration and 3 outcomes: coparenting, engagement in activities with the child, and contact with the child (Geller and Garfinkel, 2012; Turney and Wildeman, 2012; Waller and Swisher, 2006; Woldoff and Washington, 2008). Generally, researchers find a negative association between fathers' prior or recent incarceration and each of these behaviors.

Waller and Swisher (2006) detect a negative association between contempo and by incarceration and father-child contact and engagement that is mediated by the father-mother relationship. Similarly, using more rigorous methods and controlling for characteristics likely to be associated with both criminal justice contact and family stability, Geller and Garfinkel (2012) find reductions in male parent-child contact for resident and nonresident fathers who become incarcerated and weaker coparenting relationships with the child'southward female parent post-obit release. Turney and Wildeman (2012) use a variety of estimation strategies, including lagged dependent variables, fixed furnishings, propensity score matching, and conditioning on ever-incarcerated fathers. They observe that amidst fathers who were living with their children, the negative effects of incarceration are robust beyond all measures of interest (engagement, shared responsibility in parenting, and cooperation in

Suggested Commendation:"9 Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United states: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Printing. doi: 10.17226/18613.

×

parenting) and all strategies. They find further that lower levels of father involvement are due to changes in the quality of the parental relationship, changes in fathers' economic weather, and changes in fathers' health. Effects are similar across racial/ethnic groups. These researchers also examine the furnishings of fathers' incarceration on mothers' parenting and notice that they are much weaker. Amid fathers who were not living with their children prior to incarceration, however, the furnishings are smaller and disappear in stock-still furnishings and other models. The latter finding is likely due to the fact that a large proportion of nonresident fathers have no contact with their children (Amato et al., 2009). Taken together, these studies signal that incarceration reduces paternal involvement in families in which the father was living with the child prior to incarceration. A major limitation is that the analyses for incarcerated fathers are based on ane source of data—the Fragile Families Study.

Child Well-Being

Negative outcomes for children are normally reported in open up-ended interviews with fathers and their families. Mothers and some fathers believe their children perform more than poorly or accept more difficulties in school following their male parent's incarceration (Braman, 2004; Martin, 2001; Arditti et al., 2003). And many parents written report negative behavioral changes in their children, including becoming more private or withdrawn (Braman, 2004), not listening to adults (Martin, 2001), becoming irritable, or showing signs of behavioral regression (Arditti et al., 2003). Some studies also provide evidence of changes in children's emotional or mental health, with children experiencing such feelings as shame or embarrassment about their father's incarceration; emotional strain, including a belief that the begetter did non want to live at home; a loss of trust in the father (Martin, 2001); grief or depression (Arditti et al., 2003); or even guilt (Giordano, 2010).

Despite these negative experiences, periods of incarceration are not always viewed as the most challenging circumstance these children face (Giordano, 2010). A male parent'due south severe substance addiction or fierce behavior at home may lead some children to feel happier when their male parent is incarcerated. Imprisonment may requite the male parent an opportunity to receive help for his problems and even communicate more than with the child (Edin et al., 2004). In such cases, a father's release from prison may be emotionally complex, being both a happy and stressful life effect for the child.

In summary, qualitative studies for the virtually role betoken that fathers' incarceration is stressful for children, increasing both depression and anxiety as well as hating behavior. There is as well evidence that children of fathers who are violent or have serious substance abuse problems are happier when their male parent is removed from the household.

Suggested Commendation:"ix Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/18613.

×

The majority of quantitative studies focus on children's problem behaviors, which include both internalizing problems (depression and anxiety) and externalizing problems (aggression and delinquency). Early and persistent aggression and conduct issues are known to be associated with a host of negative outcomes in adulthood, including criminal behavior (Farrington, 1991; Babinski et al., 2003). A few studies investigate the influence of fathers' incarceration on physical wellness, cognitive ability, and grades and educational attainment.

The strongest and most consistent findings regarding effects of fathers' incarceration on child well-being are for behavior bug and malversation (as well run across the meta-assay of Murray et al., 2012a). Most studies examining behavior problems focus on young children. However, results of these studies mostly are consistent with those of studies looking at older children. In both age groups, researchers find that fathers' incarceration increases externalizing behaviors, peculiarly assailment.

Adjusting for other characteristics, Craigie (2011) finds a positive association between fathers' incarceration and children'due south externalizing behavior problems among blacks (see also Perry and Bright, 2012) and Hispanics, but non whites. Comparing a sample of children whose fathers were incarcerated afterwards their birth with children whose fathers had been incarcerated earlier birth, Johnson (2009) finds a positive clan betwixt incarceration and externalizing behavior, merely simply for the former children. Walker (2011) uses propensity score matching and finds a similar association with aggressive beliefs at age 5 (merely not at age 3, when aggressive behavior is more common). Using like methods, Haskins (2012) finds a positive association between fathers' incarceration and externalizing beliefs and attention problems at historic period 5. Using a serial of placebo tests, stock-still furnishings models, and propensity score matching, Wildeman (2010) finds that paternal incarceration increases concrete aggression amongst boys merely not girls (encounter besides Geller et al., 2009), particularly amongst children whose fathers were incarcerated for a nonviolent crime or were not calumniating to the kid's female parent prior to incarceration. Using a like ready of tests, Geller and colleagues (2012) find that the effect of incarceration on young children's aggressive behaviors is nearly twice as large for boys every bit for girls, but meaning for both genders; they find meaning (though weaker) furnishings for fathers who were not living with their child prior to incarceration. Aggressive behavior is much more than common among boys than among girls in this age group, which may business relationship for the gender difference in children's response to male parent's incarceration. Finally, Wakefield and Wildeman (2011) find that across all age groups (young children to young adults), fathers' incarceration increases aggression, especially amidst boys.

These researchers observe no evidence that increased beliefs problems and aggression resulting from paternal incarceration differ by race. However,

Suggested Commendation:"9 Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: ten.17226/18613.

×

they practise note that in cases in which there is a history of domestic abuse, paternal incarceration may really reduce aggressive behavior in children. These findings are consequent with enquiry of Jaffe and colleagues (2003) showing that children's response to their male parent'due south exit from the household depends on the nature of the female parent-begetter relationship, and suggest that the association betwixt incarceration and assailment is complex.

Some other type of problem behavior examined by researchers is delinquency, specifically amongst older children. Using nationally representative longitudinal data, Roettger and Swisher (2011) observe fathers' incarceration to exist positively associated with the propensity of adolescent and young adult males for malversation and risk of arrest. They find no interactions with race or ethnicity and annotation that father's incarceration both before and afterward birth is associated with these outcomes, although the relationships are stronger when the incarceration occurred during the child's life. Using data from the Pittsburgh Youth Study, Murray and colleagues (2012b) find that parental incarceration is not associated with boys' marijuana use but is positively associated with theft; in this study, the associations are stronger among white than amidst black youth. Parenting and peer processes following parental incarceration explained virtually half of the association. Neither of these studies examines the effect of fathers' incarceration on delinquency amid adolescent girls. Using a nationally representative sample of Dutch men convicted in 1977, van de Rakt and colleagues (2012) find a moderate positive association between paternal imprisonment and kid convictions (odds 1.2 times greater than for children whose fathers never went to prison). The effect was peculiarly pronounced when the father was imprisoned before the child's 12th altogether. Once again, this study is noteworthy considering information technology is able to approximate the event of incarceration internet of conviction.

The testify for children's internalizing behavior (low and anxiety) is more mixed. Craigie (2011) and Geller and colleagues (2012) find no evidence of an consequence on internalizing behavior among immature children. Similarly, Murray and colleagues (2012b) find no meaning influence on low amongst adolescents. In dissimilarity, Wakefield and Wildeman (2011) detect that paternal incarceration increases internalizing behavior among adolescents and young adults. Part of this disparity in results may exist due to the fact that internalizing of issues (depression) oftentimes does not appear until boyhood.

2 studies examine the effects of incarceration on children's physical health. Using country and twelvemonth fixed effects, Wildeman (2012) finds that paternal incarceration increases the gamble of early on baby mortality, but only amongst infants whose fathers were not calumniating. Similarly, Roettger and Boardman (2012) find that fathers' incarceration is positively associated with higher body mass alphabetize (BMI) in immature adult women, an outcome that operates primarily through depression. Foster and Hagan (2007) find evidence that

Suggested Citation:"9 Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Quango. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the The states: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/18613.

×

fathers' absenteeism due to incarceration increases daughters' risk of concrete and sexual abuse and neglect.

Finally, a few studies examine the effects of fathers' incarceration on children'southward cognitive ability and bookish performance, with somewhat mixed results. Using propensity score matching, Walker (2011) finds a negative result of incarceration on cognitive ability at age 5, whereas Haskins (2012) and Geller and colleagues (2012), using similar and more rigorous methods, find no effect at age 5. Murray and colleagues (2012b) find no relationship between parental incarceration and academic operation afterward adjusting for youth behavior prior to incarceration. Hagan and Foster (2012) detect a negative association between fathers' incarceration (at the individual and school levels) and children's grade indicate average (GPA), educational attainment, and college completion. Finally, Foster and Hagan (2009), using matching techniques, find a negative effect of incarceration on years of education, even afterwards adjusting for GPA and other characteristics, with variation by race/ethnicity. On balance, the findings for education propose that insofar as fathers' incarceration has a causal effect on educational attainment, it operates primarily through behavior bug and socioemotional adjustment rather than through cerebral ability.

INCARCERATION OF MOTHERS

More than 200,000 women are in jails or prisons in the Us, representing nearly one-third of incarcerated females worldwide (Walmsley, 2012). The past three to 4 decades have seen rapid growth in women'southward incarceration rates—a ascension of 646 percentage since 1980 compared with a 419 per centum rise for men (Mauer, 2013; Frost et al., 2006). Prior to 2000, near of this growth occurred among African American women. In 2000, blackness women were imprisoned at six times the rate of white women (Guerino et al., 2011; Mauer, 2013). Between 2000 and 2009, all the same, the rate declined for black women past 31 per centum while continuing to increase for white and Hispanic women (by 47 and 23 per centum, respectively). Mauer (2013) suggests that much of this recent shift was due to a reduction in drug-related incarcerations amidst black women and an increment in methamphetamine prosecutions among white women.

Every bit the charge per unit of women's incarceration has grown, and so has the risk of maternal imprisonment (Kruttschnitt, 2010). One in xxx children born in 1990 had a female parent incarcerated past age xiv, compared with one in 60 born in 1978 (Wildeman, 2009). Scholars have been examining the experiences of incarcerated women and their children for decades, with a majority of studies using small convenience samples and qualitative methods (for reviews, run across Bloom and Chocolate-brown, 2011; Henriques and Manatu-Rupert, 2001; and Myers et al., 1999). These studies highlight the prevalence of economic and

Suggested Citation:"9 Consequences for Families and Children." National Inquiry Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the U.s.: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/18613.

×

educational disadvantage, substance use, mental illness, and domestic corruption amongst mothers with an incarceration history, with some mothers portraying jail or prison every bit a "safe haven" from battering and problems related to substance addiction (Richie, 1996; Greene et al., 2000; Henriques and Jones-Brown, 2000).

Nearly two-thirds of mothers in state prisons were living with their kid(ren) prior to their incarceration, many in single-parent households (Coat and Maruschak, 2008; Mumola, 2000). Thus, a predominant theme in the literature on incarcerated mothers is female parent-child separation. Using single-prison samples, Poehlmann (2005b, 2005c) describes the initial separation as ane of intense distress for both mothers and children (run across also Fishman, 1983). During the incarceration period, mother-child contact may be limited every bit a result of travel costs or mother-caregiver relationship issues (Bloom and Steinhart, 1993; Hairston, 1991). Less mother-child contact may exist associated with mothers' increased depressive symptoms (Poehlmann, 2005b). Other studies observe that maternal incarceration is associated with a host of negative child outcomes, including poor academic operation, classroom behavior issues, break, and delinquency (see the review of Myers et al., 1999). Poehlmann (2005a) examines the part of caregiver arrangements and modified domicile environments during mothers' incarceration and finds that amid children of incarcerated mothers, cerebral outcomes may be influenced by caregiver socioeconomic characteristics and the quality of the domicile environment. This topic claim more attention in future research.

A few contempo studies use longitudinal data and more rigorous methods to examine the effect of maternal incarceration on kid bookish functioning, housing arrangements, and behavioral outcomes. Using data from ii large samples of children in Chicago public schools and propensity score and fixed effects modeling techniques, Cho (2009a, 2009b) finds no association between maternal incarceration and children'south standardized test scores, merely a negative effect on grade memory in the years immediately following female parent's prison entry. Another report (Cho, 2011), using administrative records and result history analysis, finds that adolescents are at college chance of dropping out of school in the year their female parent enters jail or prison.

2 studies utilise data from the Frail Families Study to examine the event of maternal incarceration on housing instability. Geller and colleagues (2009) find that incarceration is associated with an increase in the likelihood of residential mobility. Wildeman (forthcoming) finds no upshot on child homelessness. This latter finding may be due to the fact that children of incarcerated mothers are more likely than children of incarcerated fathers to enter foster intendance (Dallaire, 2007; Mumola, 2000).

Finally, Wildeman and Turney (forthcoming) use data from the Frail Families Written report to examine the event of maternal incarceration on child

Suggested Citation:"9 Consequences for Families and Children." National Enquiry Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United states: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/18613.

×

beliefs problems. Using propensity score models for both parent and teacher reports, they detect no association between mothers' incarceration and children's behavior bug at age 9. Dallaire (2007), however, finds that developed children of incarcerated mothers are more likely than adult children of incarcerated fathers to exist incarcerated.

Taken together, and then, the small-scale amount of show on the outcome of maternal incarceration on overall child well-being is mixed. This discipline, too, deserves more attention in future inquiry.

METHODOLOGICAL LIMITATIONS

To put the higher up discussion in proper context, information technology is important to annotation the major limitations of the studies reviewed. First, all of the ethnographies and many of the quantitative studies are based on convenience samples obtained in specific cities or communities. While these studies provide rich descriptions of the family lives of men and women with an incarceration history, and while they generate a multitude of intriguing hypotheses, their findings may not be generalizable to families in other cities or other parts of the country.

Second, although a number of more recent quantitative studies apply probability samples of the national population, these studies are based on only three data sets: the Delicate Families Written report, the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Wellness, and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. At this time, these are the only big, nationally representative information sets that include data on incarceration. The field would benefit and more would be known about outcomes for families if other large national surveys did more than to capture data from families with incarcerated or previously incarcerated parents.

A tertiary limitation involves the measurement of other criminal justice contact or criminal behavior. With a few exceptions, studies do not accept account of factors that precede incarceration (offending, arrests, and convictions), so the consequences of imprisonment are non sharply distinguished from those of other factors.

A fourth, and peradventure near important, limitation of the literature is that all of the studies are based on observational rather than experimental information. Men who go to prison are unlike from other men in ways that are probable to touch on their family relationships also as their chances of incarceration. Every bit noted elsewhere in this report (run across Chapters two and 7), men and women with an incarceration history are less educated and more likely to accept mental wellness problems and booze and drug addictions than the full general population. In turn, their families are likely to be unstable and to experience economic hardships and their children to be at risk of doing less well in school regardless of whether the father or mother spends time in jail;

Suggested Citation:"9 Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Quango. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/18613.

×

BOX 9-two

Techniques for Dealing with Omitted Variable Bias

Researchers use a multifariousness of statistical techniques to deal with the problem of omitted variable bias. The oldest and most widely used is to control for all of the characteristics that might bear upon both incarceration and family well-existence. Unfortunately, this technique is limited because the data sets available for examining the effects of incarceration practice not measure out all the relevant characteristics.

A 2nd technique is to mensurate the outcome variable of interest earlier and after fathers' incarceration to encounter whether spending time in prison is associated with a change in the outcome. This approach—the lagged dependent variable (LDV) model—requires longitudinal data and allows the researcher to gauge the effect of incarceration cyberspace of the factors that touch on the preincarceration issue. In one of the studies nosotros examined (Geller et al., 2012), for example, the researchers controlled for children's behavior bug at historic period three and looked at whether those whose fathers went to jail or prison when the children were betwixt ages three and 5 were more likely to showroom behavior problems at age 5 than those whose fathers did not go to jail or prison house. Longitudinal data also permit the researcher to deport a placebo test to see whether fathers' future incarceration predicts current family bug. In the case given in a higher place, the researchers looked at whether children whose fathers were incarcerated when the children were between ages 3 and five showed higher levels of behavior problems at age 3. A positive effect would signal that something other than incarceration was causing the behavior problems.

Other researchers use longitudinal data to estimate a fixed furnishings model, which examines the association betwixt a alter in incarceration and a alter in behavior. While this model does a better job than the LDV model of decision-making for omitted variable bias, it does non eliminate the possibility that a alter in an omitted variable might have led to the incarceration as well equally the change in behavior. Continuing with the previous example, a father might have go

that is, the correlation between incarceration and family hardship may exist due to conditions other than incarceration. The failure to take account of characteristics that affect incarceration also as social and economical hardships leads to what researchers phone call "omitted variable bias." This problem is endemic in the literature on incarceration effects.

The all-time way to deal with omitted variable bias is to run an experiment in which people are randomly assigned to incarceration status. Considering people cannot be randomly assigned to prison,two researchers have used a

_________________

iiNote, however, that some studies have tested an overnight stay in jail as treatment (Sherman and Berk, 1984). In their study of constabulary interventions for family violence, Sherman and Berk (1984), for example, found that a nighttime in jail was not strongly associated with reduced offending. In addition, researchers accept considered differing practices as natural experiments. In a contempo study, Loeffler (2013) used randomization to judges, which led to variation in time

Suggested Citation:"ix Consequences for Families and Children." National Inquiry Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Printing. doi: 10.17226/18613.

×

unemployed during the 2-year menses after the kid reached age iii and earlier age five and responded past engaging in criminal activity that ultimately led to incarceration. In this case, the father'south unemployment and criminal behavior may also take a function in the child'due south increasing behavior problems, or may be the main causes rather than incarceration.

A 5th technique is to employ a land policy, or natural experiment, to gauge the event of incarceration on family well-existence. For instance, several researchers have used state differences in race-specific incarceration rates to determine whether these policies and practices bear upon family unit formation behaviors, such as marriage, divorce, and nonmarital childbearing. By using a state-level measure out of incarceration, the researcher avoids the problem of omitted variable bias at the individual level. But the problem all the same exists at the aggregate level unless the researcher can detect a policy or do that affects an individual'south chances of incarceration simply is unrelated to the event of involvement except via this pathway.

Finally, some researchers use a propensity score matching approach, which entails calculating a probability of incarceration for each homo (or father) in the study, and then comparison the family outcomes of men with the same probability (or propensity) just different incarceration experiences to run across whether they differ. Although this arroyo does non bargain with omitted variable bias—propensity scores are based on observed variables but—it has certain advantages over standard regression analyses and may yield more accurate estimates of the association between incarceration and outcomes of interest. One of the more disarming studies is one that starts with a sample of bedevilled men, constructs a matched sample of men with the same propensity for incarceration, and then looks at whether those who were incarcerated had different outcomes than those who did not go to jail or prison (Apel et al., 2010). This study institute that men who were incarcerated were more than likely to divorce than their counterparts who were non incarcerated.

variety of statistical techniques to deal with the trouble of omitted variable bias (see Box ix-2).

Cognition GAPS

As discussed above, the studies reviewed in this affiliate take several limitations. A more than robust research program is needed to respond the questions considered hither with greater confidence. We offering the following observations on how to accost some of the knowledge gaps in this expanse.

___________________________________________________

served, to assess the furnishings of incarceration on law-breaking and unemployment. While this arroyo has limitations, it would provide boosted information to be considered along with findings based on the other approaches to dealing with omitted variable bias.

Suggested Citation:"9 Consequences for Families and Children." National Enquiry Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United states of america: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: x.17226/18613.

×

Agreement Variations

More work is needed to sympathize how the furnishings of fathers' incarceration on families and children vary depending on living arrangements prior to incarceration, the quality of relationships, and the ages and developmental stages of affected children. Information on the level of interest and quality of the parental relationship prior to conviction could be incorporated into an experiment, as well equally longitudinal data collection. Annotation, yet, that measuring fathers' residence would exist a challenge because men who are probable to spend time in prison and jail as well are likely to be involved in multiple households earlier and after release.

Notwithstanding missing is important descriptive information that bears on the causal questions at hand. The field would benefit from tackling the trouble of omitted variables by observing them. How dangerous, fierce, drug involved, and/or mentally unstable are the individuals who get to prison? What do their personal histories (as children) of family instability and family violence look similar? How does incarceration contribute to family unit complexity—multiple partners, attachments, and households?

The drove of longitudinal information tracking individuals before and subsequently their contact with the criminal justice system is needed. Partnering with existing longitudinal studies would be a useful avenue to explore to this stop. Indicators of the quality of family life need to be tracked to better understand the influences on spousal and/or parental behaviors.

Aggregate Furnishings

Little attention has to engagement been paid to estimating the aggregate effects of high rates of incarceration on family unit stability, poverty and economic well-beingness, and child well-being. Given that incarceration is full-bodied among men with low instruction, one might expect that contempo trends in incarceration have affected aggregate poverty rates as well every bit trends in family structure and intergenerational mobility. To address aggregate effects, better estimates are needed of the proportion of families and children exposed to incarceration and the differential furnishings of incarceration depending on living arrangements and the quality of preincarceration relationships. Estimates also are needed of the proportion of families likely to do good from a family unit member'due south incarceration.

CONCLUSION

This affiliate has reviewed the literature on the consequences of parental incarceration for the children and families of those incarcerated,

Suggested Citation:"9 Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/18613.

×

a question of importance at any level of incarceration but peculiarly in the current era of high U.S. incarceration rates. Our literature review has included both recent ethnographic studies and quantitative analyses and studies using convenience samples as well as population-based samples. Such a review represents a partial await at the literature on the consequences of incarceration for families and children; a more thorough review would be beyond the scope of this study. Notwithstanding, our review suffices to provide a sense of the consequences. Although the testify from private studies is limited and findings across some studies are mixed, our review leads to the conclusion that parental incarceration, on balance, is associated with poorer outcomes for families and children. Whether these associations reflect causality is much less certain.

We find consistent testify, in both the ethnographic and quantitative studies, of a link between men's incarceration and instability in male-female unions. We notice a strong and consistent link between fathers' incarceration and family unit economic hardship, including housing insecurity, difficulty meeting basic needs, and use of public assist. Incarceration tends to reduce fathers' involvement in the lives of their children after release, in large function because it undermines the coparenting relationship with the child's mother. Finally, both ethnographic and quantitative studies bespeak that fathers' incarceration increases children's behavior problems, notably aggression and delinquency. The consequences are peculiarly pronounced among boys and among children who were living with and positively involved with their father at the time of his incarceration. Recent surveys indicate that roughly 4 of 10 incarcerated fathers written report living with their children prior to incarceration. Of involvement, although father's incarceration is associated with poorer grades and lower educational attainment, it is not associated with lower cognitive power. Rather, school failure appears to arise from social-emotional problems rather than a lack of intellectual chapters.

In reviewing the literature on the consequences of parental incarceration for the families and children of those incarcerated, we have been mindful of the broad charge to this committee. Ideally, the research evidence would help in determining whether the dramatic increment in incarceration rates over the by four decades, viewed every bit a distinct phenomenon, has affected, for better or worse, the families and children of those incarcerated. There are, yet, no studies explicitly examining the effect of the prison buildup on the families and children of incarcerated parents. As a statistical matter, the number of children with a parent in prison continued to grow with increasing incarceration, reaching an estimated one.7 meg in 2007. Thus we might hypothesize that greater numbers of individuals and families take experienced the predominantly negative consequences of a partner'southward or

Suggested Citation:"nine Consequences for Families and Children." National Research Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: ten.17226/18613.

×

parent's incarceration as the extent of incarceration has expanded, but that hypothesis has not been tested. There remain unanswered questions about the aggregate effects of the incarceration buildup. Nonetheless, the close correlation between having a partner or parent who has been incarcerated and poor outcomes amongst families and children is unmistakable.

Source: https://www.nap.edu/read/18613/chapter/11

0 Response to "Adolescents From Divorced Families Frequently Display All of the Following Negative Effects, Except:"

Post a Comment